The art of Ancient Egypt extends over a period of more than 3000 years. Ancient Egyptian art is very distinctive and easy to recognize. Although the art has evolved, it is also conservative, and several key elements and principles remain throughout the period. Particularly typical is the use of profile in the two-dimensional art and the strict, frontal representation of the human body in statues.

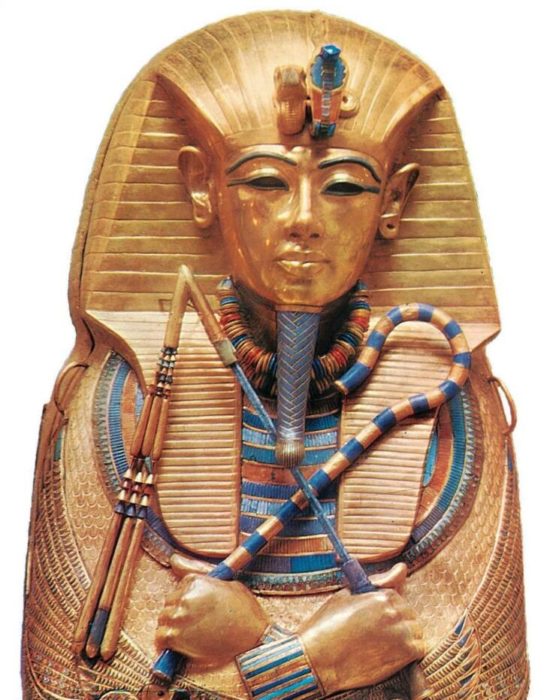

Tutankhamon’s gold arcs, solid gold, faience, glass flux and semi-precious stones. Height 184 cm. The king holds scepter and whip in his hands. 18th dynasty. The Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

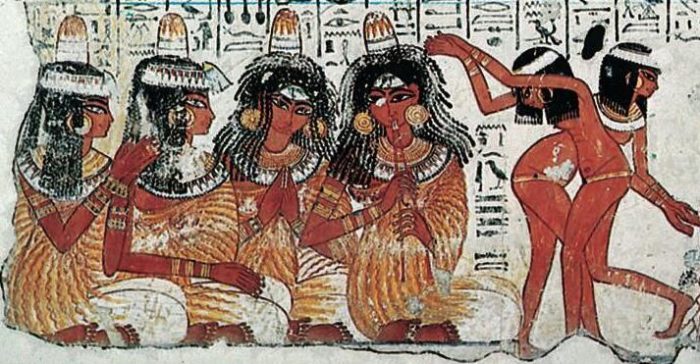

Dancers and musicians, mural from a tomb in Teben. 18th dynasty. British Museum, London.

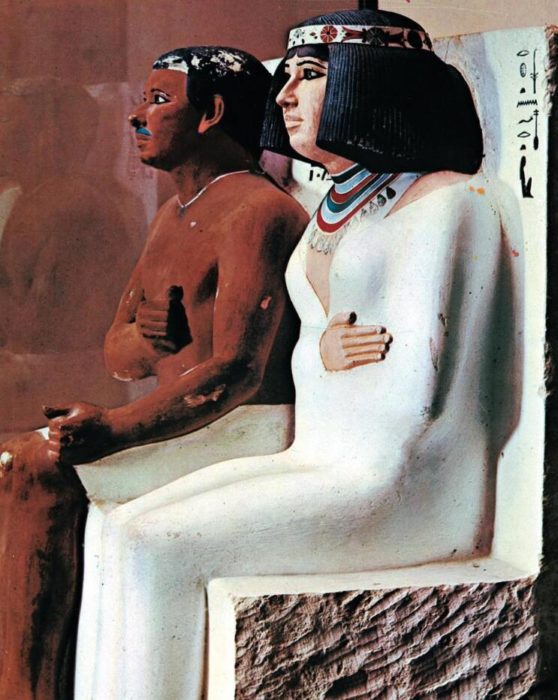

Sculpture depicting Prince Rahotep and Princess Nofret. Painted limestone, height 120 cm. 14th dynasty. Found in the Prince’s tomb in Meidum. The Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

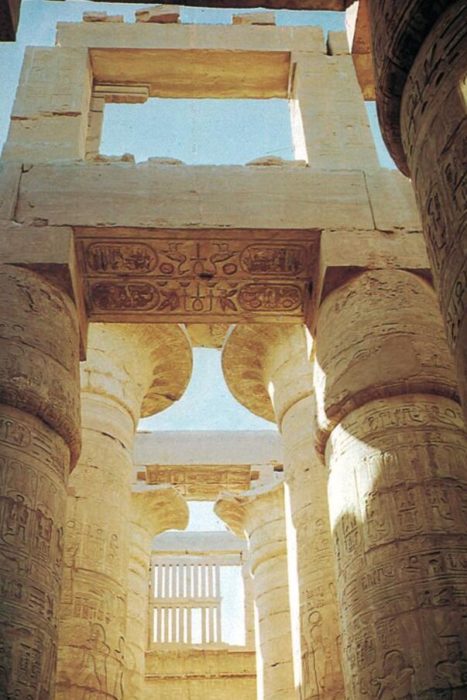

Column hall in the temple of the god of Amon in Karnak. This hall, which has 140 columns, was built under Seti 1 and Ramses 2.

Chestnut from Tutankhamon’s grave. 18th dynasty. The jewelry is the only thing left intact. The Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

Ancient Egypt is also known for its monumental architecture in stone, especially the pyramids of the ancient kingdom, the great temples of the new kingdom and the royal and private rock tombs of the new kingdom.

Predynastic and Early Dynastic (2543 BCE)

Two red-necked geese and a gray goose, part of a mural with animal paintings in Meidum. Early 4th Dynasty. The Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

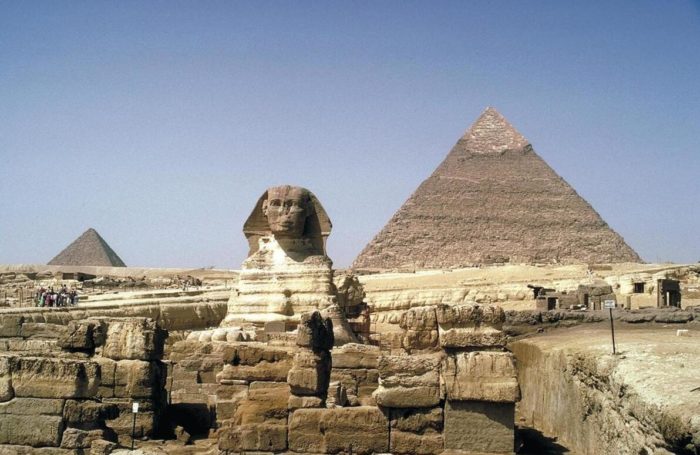

Khefren’s pyramid at Giza outside Cairo, with the sphinx in the foreground. In the background to the left you can see Mykerinos’ pyramid, the smallest of the three major pyramids.

From this period small figures, often very expressive, of animals and people in clay or ivory, as well as relief- adorned objects such as chambers and knife shafts in ivory and slate make-up palettes, have been preserved. In particular, the latter have been performed with great care and are highly artistic.

The pottery is decorated with dark figures on a light bottom. The motifs are partly geometric figures and partly stylized people and animals. During the first two dynasties (c. 2900–2543 BCE ), artistic development continues from the predynastic period.

The Ancient Empire (c. 2543–2120 BCE)

Queen Hatshepsut’s temple facilities at Teben.

Under the old empire, monumental visual arts and architecture flourished. The art is subject to burial or religious purposes. Some of the most impressive tombs come from the Old Kingdom. To this era belong the great pyramids of Sakkara and Giza, with associated temples and other buildings (the great sphinx of Giza belongs to King Khefren ‘s tomb complex).

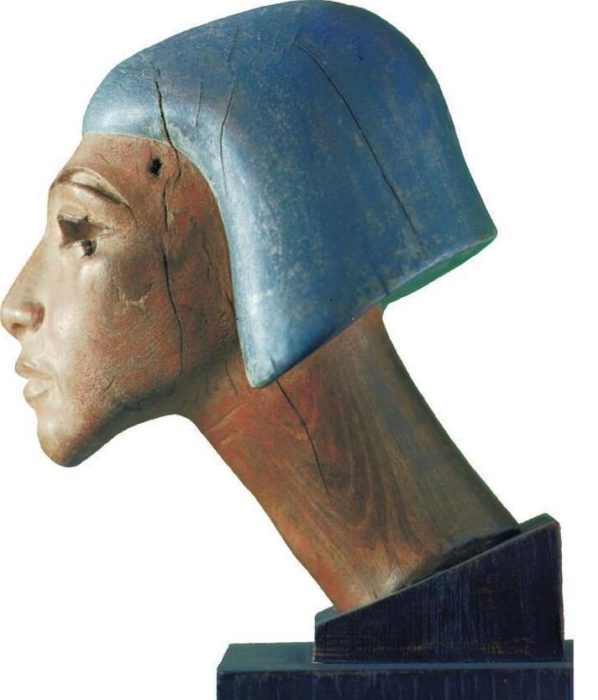

The pyramid, which houses the pharaoh ‘s mummy, is developed by the so-called mastaba, a tomb where the walls are sloping inward as on the lower part of a pyramid. The ceiling is flat. The dead man lay in a burial chamber under the mastaba. Some mastabas have several inner rooms, but two were essential, a chapel and a serdab, a room containing statues of the dead. These had to be portrait-like, since the deceased’s ka (a term which is translated inaccurately by soul ) should be able to reside in them. Actually could take up residence in the body of the dead, which was embalmed and carefully protected from destruction, but if the mummy destroyed, the portrait statues could be used instead.

The portrait statues were constructed according to a strict frontal form that became the determinant of later Egyptian art just to Roman times. Standing statues have left legs set forward. Sitting statues are either made throne with parallel legs or sitting on the ground with crossed legs or in a kneeling position. Standing stone statues (the materials vary from limestone and sandstone to harder rocks such as granite ) have a backing, while wooden and metal statues lack this. Statues in the latter materials are rare, but can be cited as an example of a copper statue of Pepi 1 (ca. 2276–2228 BCE).

The statues of God are made on the same form as the portrait statues, except that the head is idealized. Several gods are also presented with animal heads or in complete animal form. The rooms inside the tombs of the old kingdom are decorated with reliefs. They were painted, as was the case with the statues. Due to their polychromy and flatness (sometimes cut into the background, so-called negative relief), the reliefs are very close to the surface art.

The reliefs are people are prepared in a perspective which were also common in other old Høykulturer which the Mesopotamian or archaic Greek, with head and legs in profile, shoulders and chest from front waist portion in the 3/4 profile. The eye is unlike the other facial features seen from the front. When it came to slaves and other low-ranking people, one could move from this perspective and into a more lively and naturalistic representation. The same was true of depictions of animals, which often reveal fine nature. Common in Egyptian flat art is also the perspective of importance, where more important people are produced on a larger scale than the others.

The motifs are often sacrificial offerings to the deceased or scenes from daily life that one hoped would repeat in the hereafter. The many small models of houses and boats and statuettes of servants and livestock found in Egyptian tombs have the same symbolism. An integral part of flat art is hieroglyphs, itself a pictorial. Many of the characters are independent works of art.

The Middle Kingdom (c. 1980–1760 BCE)

The portrait statues of the 11th and 12th dynasties are particularly high. Several of them have a melancholy and tired expression, especially the statues of King Senuseret 3. This can symbolize an earnest king burdened by the duties and worries of power.

In the sculpture one can also notice a tendency to preserve an idea of the original stone block the sculpture is carved out of. Some figures, especially sitting ones, are somehow not released from the block.

The New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069 BCE)

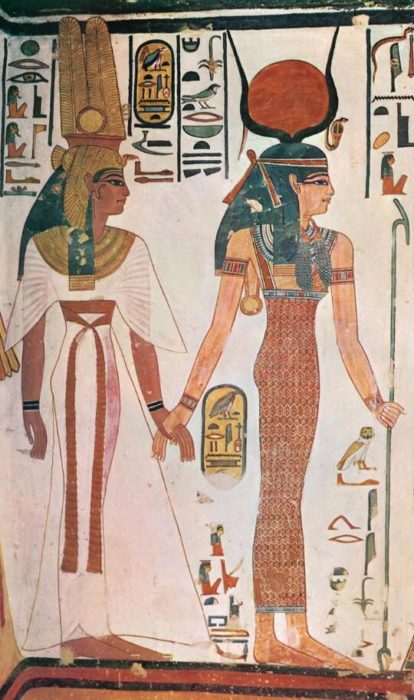

Queen Nefertari, Ramses 2’s Queen (19th Dynasty) is led by Isis in a relief from Nefertari’s tomb in the Queen’s Valley at Teben. Nefertari wears the feather crown of the goddess.

The New Kingdom art builds on the stylistic principles of the past with great technical mastery and security. Details, such as coat folders and hair locks, are given great weight and often have a decorative touch. Compared to previous eras, the new realm’s artwork seems lighter and more elegant, but this can go into pure exterior, smoothness and monotony. The latter can be seen particularly clearly in the colossal statues and the great temple reliefs with their endless sacrifice processions and depictions of Pharaoh’s campaign.

During the 18th dynasty, Teben became the capital of the entire kingdom. In and around the city center, a number of beautifully decorated temples have been preserved, such as the Luxor and Karnak temples on the east bank of the Nile and the tombs of Hatshepsut, Ramses 2 and Ramses 3 on the west bank. Here also lies the Valley of the Kings, where the pharaohs were buried in rock graves. With the exception of Tutankhamon’s tomb, all have been plundered in antiquity, so that only the richly painted decorations testify to the splendor of the past. In the burial grounds of the Qurna officials, distinguished families’ graves are scattered across a larger area. The paintings in these tombs are often of the same quality as those in the Valley of the Kings.

A peculiar interplay in the art of the new kingdom forms the Amarna era under Pharaoh Akhenaten (c. 1353–1336 BCE). In the context of the religious upheaval, visual art breaks with previous traditions. As a result, it gains greater freedom and freshness, which is particularly evident in nature studies. On the other hand, the art of Amarna is not free from dull features, such as when the royal peculiarities of the royal family are exaggerated and, moreover, transmitted to the representations of court people and dignitaries. Due to its originality, the art of Amarna has been given much attention, but in Egyptian art history it is only a parenthesis. The style is partly left behind a short time after the Akhenaten, under Tutankhamon. Then the style returns to the old. Tutankhamon is particularly famous because his tomb with all its magnificent tombs was preserved to our time. The items show how high the furniture and goldsmiths reached Egypt.

Third Transition Period and Sendynastic Time (1069–332 BCE)

Ramses 2’s tomb temple, Ramesseum, on the west bank of the Nile at Teben, 19th Dynasty.

The art of the third transitional period and the transmigratory era shows strong tendencies to emulate the style of earlier periods, both in terms of proportions and design. This is especially common in the 25th and 26th dynasties, where the statues of the old kingdom were imitated. From this time there are also several examples of reuse and recycling of past art. For example, a sarcophagus from the tomb of King Merenptah of the 19th Dynasty was moved to Tanis and reused by King Psusennes 1.

From the third transitional period several good examples of very high quality metal art have been preserved. Here can be mentioned the silver sarcophagi to King Psusennes 1 and Sheshonk 2 from the royal tombs of Tanis.

Greco-Roman times (332 BCE – 395 BCE)

With the Greek influence in Egypt, which became especially strong during the Ptolemies (304-30 BCE), pure Greek works of art in the Hellenistic style were created, partly a mixture of art that shows both Greek and Egyptian features and partly traditional Egyptian style. This pattern continued into Roman times, although the pure Egyptian style eventually gave way to Greco-Roman impulses.

During Roman times, Egyptian art gained local features, such as a stronger degree of linearity and abstraction. This style forms the basis of Coptic art in ancient Christian Egypt. Coptic frescoes (the monasteries of Bawit and elsewhere) and textile arts are particularly high. Coptic art remained, albeit in a reduced version, even after the Arab conquest of Egypt about 640 AD.